At the beginning of 2020, right in the preparation phase of AMRO Art Meets Radical Openness, social distancing became the new context in which servus.at had to produce its community festival. Sad about the amount of lifes taken away by the pandemic and worried for the implications of the quarantine, servus.at decided that especially because of the situation it was important to organize our biennial gathering as a remote event.

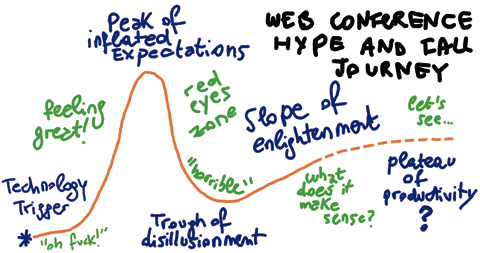

Using as inspiration the graphic of the »hype cycle« of technologies patented by the american consulting firm Gartner,[1] we describe how social activities boomed on video call and streaming platforms and how this maybe influenced our experiment of a »radical digital festival«. A note to the reader: this article was written before the beginning of AMRO festival, but it was distributed after the event. Only you can make now the connection between what is written here and what you, hopefully, experienced during the festival.

Technology trigger: »let’s just meet online«

Social distancing was a perfect trigger for a new wave of adopting web conferencing. The infrastructure has been there for a long time, but until right before the isolation measurements, a majority of people – many producers of art included – were still reluctant to fully embrace these tools for production and for reaching the audience. The smooth acceptance of the new working condition was particularly surprising: everyone immediately moved any public activity that could be virtualized »online«. Various strategies were involved: some of us retrieved the forgotten credentials of obsoletes accounts; others experimented each day with new platforms and ended up with a dozen of new accounts and installed software, each of them used with a very specific group of people.

Such a dissociative approach towards platforms was intense, but nothing new. The issue of synchronizing people in digital spaces is well known, as well as the speed at which people develop habits and make digital rooms become »familiar places«. The power of platform affection that emerges, when any group decides to move to a new tool for any given reason is most of the time underestimated: everyone feels left out, unsure if the meeting happens in »the new« or in »the old place«. The recent overload of channels and rooms was especially strenghened by a new unwritten social rule that was identified only now. It says: »if a platform is proposed for a meeting, this platform shall be used and not changed – unless for serious reasons«. Sadly, privacy and data protection are seldom relevant reasons, if that platform offers a face recognition algorithm that puts bunny ears on your head.

Despite all this, overloaded by new subscriptions, many still embraced cooperatively the situation and each of us started feeling – at least a little bit – like a promising youtuber.

Peak of Inflated Expectations: »this will change everything«

Over the first days, except for the anxiety of the pandemic, everything ran great on the desks of contemporary festival workers. Seven 2-hour meetings per day were followed by a web-bar with friends in which the most recurrent remark was »why didn’t we do it before?«

This peak of enthusiasm screwed up even the very separated castes of the »apocalypti« and the »integrated ones«, the two opposing socio-technical groups first labeled by italian semiologist Umberto Eco in the 60s.[2] The old school intellectuals who did not consider the potential of new technologies in their work were »apocalyptic«, whereas the »integrated« were the ones that showed a more open interest towards upcoming media culture – and were marked as »too uncritical« from the first group. In an almost perfect conceptual loop, the rising mass culture appropriated and decontextualized Eco’s reflection on how academics dealt with the time in which they were living and the terms labeled the ways in which people approached web conferencing until covid-19 came.

For many, this peak of streaming platforms and virtualized concerts finally realized the long awaited marriage of online technologies and generally large audiences. Large museums made their collections online available for free, musicians published their content freely on the web and even art galleries decided to hop into the world of virtual exhibitions. All this enthusiasm was almost mocking the efforts of countless artists that for decades tried to push the possibilities of online spaces ... but what matters is that we are there now.

The success of virtual stages also hit influential personalities of media art that had addressed for a long time the linguistic and representational limits of media and technology. Even they were attracted by the rampant virtualization as if it was as an angel announcing the transformation from society of closeness to a happy society based on distance.[3]

Through Disillusionment: Umberto’s redemption

That enthusiasm did not last long. After a couple of weeks of intense remote activities, everyone began recalling *why* remote conferencing technologies were always the second option.

The initial lightness of the audiovisual meeting was overloaded by the invisible labour behind any unspectacular online presentation. Connectivity issues at each end of the conversation were not tolerated anymore, as if everyone expected the other to have the communication skills of a well-trained journalist. On top of this, in the effort to get something meaningful out of the virtual connection, many reached the exhaustion limits of supporting exclusively-mediated relations.

After this cold shower, the most adaptive folks found ways to deal with the mutated media environment, arguably setting the basis for a career as a proto-rising-web-star. Others began escaping the virtual spaces mumbling about rare connectivity issues to avoid »yet another online call«.

Slope of Enlightenment: a slower, multilayered space is needed

2020 AMRO Festival was born in this context. As a result of this, we tried not to copy-paste the festival schedule into a »streaming timetable«, but rather follow a logic of multiple spaces that could host different encounters. The spinning of the tornado of the festival title became an inspiration for the multiple directions of sight that one has to take into consideration while dealing with contemporary platforms. But also reminded us that themes such as the climate crisis, sustainable technologies, the need for alternative internet infrastructure cannot be solved with few simple (one-sighted) instructions. This was in my opinion mirrored in a general fragmentation of the festival program into threads and conversations that cover interconnected aspects.

Rather than seeing the event as the digitalization of a single room with someone on the stage, we tried to consider the time and spaces in which spectators were living in. Presentations started before the beginning of the festival and workshops could run much longer than our four days. Contributions from individuals were mostly grouped into public, private and semi-private conversations. But most importantly, we layered digital spaces of various kinds, thinking that this multiplication of platforms could stimulate relations with different speed and deepness. And, hoping that all of this made sense, we went online. Here you can conclude the story with what you experienced during the festival, dear reader.

Plateau of Productivity: how will be go back to normality?

In the hype cycle, the first moment of enthusiasm is followed by the feeling of a big night out, after which the delusion after excitement is processed into a more mature relationship with the new technology. Following this logic, after these first experiences, we would have found ways of creating hybrid formats – integrating physical and virtual, balancing out local presence with remote impulses.

With a more »apocalyptic« tone, it is maybe easy to think that once the pandemic will be solved, very likely web conferencing will at the same time disappoint and thereby contradict the predictions of the silicon valley. In the cultural sector, everyone will be happy to go back to »normality« and appreciate the possibility of physical meetings even more than before. Simultaneously, large tech companies will consider keeping remote working forever and not going back to the »normal« office situation. An unsurprising strategy to economize infrastructural expenses further by pushing the rhetoric of having the employees work in their home environment – surely at the cost of the worker.

Only time will let the real effects emerge. But thanks to a last naive thought of an »integrated one« – the two souls are very difficult to separate indeed – I like to imagine that in some corners of the future web, thanks to this situation, a community found itself in some special digital spaces and since then can finally have the conversations that they could never have had somewhere else.

One does not simply make a zoom meeting

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hype_cycle

[2] Umberto Eco, Apocalittici e Integrati, 1964, Italian Edition; Apocalypse Postponed, 1994, English Edition

[3] »Das Corona-Virus ist der unheimliche Bote, der den Wandel von der (körper- und maschinenbasierten analogen globalen) Nahgesellschaft in eine (signal- und medienbasierte digitale globale) Ferngesellschaft verkündet.« from Peter Weibel, »Virus, Viralität, Virtualität: Der Globalisierung geht die Luft aus« in »derstandard.at«, online edition, 5. April 2020, available at https://www.derstandard.de/story/2000116482357/.

Davide Bevilacqua is a media artist and a curator interested in network infrastructures and technological activism, as well as in curatorial and artistic research about the framework conditions in which artistic practice is presented and transmitted to the audience. His current topics of research are the environmental impact of technology and internet sustainability, digital greenwashing practices and platform capitalism. Davide coordinates servus.at cultural program since 2018.

http://www.davidebevilacqua.com/

https://core.servus.at/