One of the earliest attempts to build an alternative to mainstream corporate social networks was the diaspora* project.[1] Its alpha version was released in 2010 and around 2014 the project managed to attract enough attention that it seemed like it could manage to reach mainstream adoption – with some overenthusiastic folks even talking about diaspora* as the platform that would »kill Facebook«.[2]

In a nutshell: diaspora* is a decentralized social network with a strong focus on privacy and anonymity, and is technically based on open-source software and independent nodes. The platform is composed of a multitude of »pods«, instances of the social network that are localized on independent but intercommunicating servers. A user can register to a specific pod and communicate with other users that have signed up to that instance, but also with users from other pods. Moreover, diaspora* was planned to also work as an aggregator and integrate content from other existing (micro)blogging platforms like Twitter, Tumblr and Wordpress or include web feeds like RSS or Atom. This would potentially allow new users to smoothly migrate over to the platform by importing already generated content and bring in many more people.

Such networks are described as »federations«, systems where each community is allowed to use the software and customize it to fit the particular needs of their members. This customization can range from functional changes to different types of features within the network. This creates partially autonomous, self-moderated, communal spaces in which the communities develop their own codes of conduct. Moreover, the option of exchanging content with users from other instances is always there.

After a very successful Kickstarter Campaign in 2011 and despite the early adoption of various enthusiast users, diaspora* did not succeeded in fulfilling the high expectations it generated, mostly because »there was nobody there«.[3] In an interview in 2014, one of the main developers admitted »No matter how many people joined, it still felt like a ‘ghost town’ compared with Facebook.«[4] But there were various other elements that contributed to the lack of popularity. As some early supporters reported: the platform was programmed on Ruby on Rails, a programming language not so easy to implement and customize on a Linux server. Furthermore, the planned integration(s) with other services did not appear to work as smoothly as promised and, even further, some aspects of the user interface & experience design alongside the programming were buggy and could not be solved in a reasonable time by the developers.[5]

Together with these and probably many other reasons, the magic »network effect«, the special ingredient behind the success of Facebook and Twitter, was not there. Therefore, many of diaspora*’s users, disillusioned, either moved to the next promising non-corporate project or back to the unsatisfying world of data-capitalizing platforms where – »at least« – they could reach a large number of readers with their content.[6] At the moment diaspora* is still online, but it seems to not reach much out of its niche of aficionados.

Over the last couple of years, the scene witnessed an emergence of another wave of alternative, decentralized, social platforms. All of which were released and developed with ideas similar to the ones of diaspora*, such as the federated model, cross-platform communication and a strong focus on privacy.

In their cases, the obvious question is: are they going to make it? Or become »another diaspora*«?

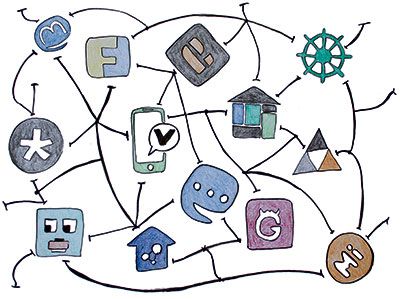

As most of us already know, the FLOSS (Free/Libre and Open Source Software) community always works to build alternatives to the corporate web. This time the situation might be different (arguably this sentence can be used for any release of any FLOSS software, so I’ll leave it in italic). Indeed, thanks to the infinite number of scandals involving corporate social media platforms,[7] finally more individuals seem to long for more ethical, private and sustainable social networking platforms. This created the perfect conjuncture for an explosion of projects such as Mastodon (mastodon.social), PeerTube (joinpeertube.org), PixelFed (pixelfed.org), or Plume (joinplu.me).

These are only a few of many platforms that comprise the freshly branded »Fediverse«[8], the universe of federated servers used for web publishing and file hosting. They are based on open-source protocols, like ActivityPub or OStatus, which are responsible for the interoperability between platforms. Each service is specialized in different media and various types of content such as video, sound, images or text; just like mainstream social media platforms: Facebook, Instagram, YouTube or Tumblr. Probably even »too much alike«, which could be the first critique meant towards what otherwise appears as a very coherent and structured movement for an open web.

Although we do not have enough space to cover it here, another critical issue related to this »new wave« is what can be described as a »naivety« in some FLOSS projects. If a specific software is open-source and non-corporate, it does not mean that it cannot be used for different intentions than the »openness« in which it was produced. We can use the alt-right platform Gab as an example, which in 2019 switched its software to a modified version of the open-source Mastodon.[9] Moreover, a delicate aspect of this is that these projects are often developed by a very small group of passionate programmers. And when you have multiple programmers working on the same code, the probability of including code-biases in the FLOSS scene is as high (if not higher than) as the corporate world.

But coming back to one of the big topics of the FLOSS community now, is how to balance the references between what we, the open-source programmers and their supporters, do and what they, »the big grey capitalist tech corporates«, do. In the open-source scene the topic is not a new one: why do we always have to compare our products with corporate ones and build them with similar features? Take the examples of GIMP being described as »the free version of Photoshop« or Scribus as »the open InDesign«, or Mastodon as »a better Twitter« and PixelFed as »the free Instagram«, and so on. Coming back to diaspora*’s story: rumors about the platforms »failure« started circulating once they realized diaspora* could not simply substitute Facebook overnight, which was an obviously impossible task to accomplish in the first place. In this case, the tendency of constantly comparing open-source with corporate products might have contributed both to its very quick initial expansion and its sudden decline.

So, probably it is the initial »enchantment« that has to be re-formulated in the closing sentences of this article and it will be in the form of an advertisement. Do you remember the first time you used Facebook and there were only a few people you knew there? Even though I was not an early adopter, I then felt that I was part of a tighter community, much more cohesive than what it became later, when everyone was there. At the moment, joining a new, independent instance on Mastodon also feels that way: only a few people, fewer notifications, a close group of people which share some common interests and a set of good conversations. Enjoy it while it lasts, just like the current and loyal diaspora* users do, because as soon as an independent platform becomes larger and goes mainstream, many problematic patterns from Silicon Valley have the potential to emerge again. (Finally, the moment for our commercial: you can try mastodon at social.servus.at!)

And as a proper conclusion, it is worth mentioning that the battle against the corporate world does not end here. Its attempt to move the foundation underneath them advances further, this time hopefully with the development of secure, open and cross-platform tools and protocols capable of pushing corporate software towards open standards.

This Text for servus was written by Onur Olgaç and Davide Bevilacqua. The contents of the article were developed also thanks to a series of conversations with Aileen Derieg.

Many Platforms to Rule Themselves

The new wave of emerging alternative social media platforms. By Onur Olgaç and Davide Bevilacqua.

[1] https://diasporafoundation.org

[2] https://web.archive.org/web/20170123163332/motherboard.vice.com/blog/what-happened-to-the-facebook-killer-it-s-complicated

[3] https://publichistory.media/2016/02/21/distributed-social-networks-and-public-history/

[4] https://slate.com/technology/2014/10/ello-diaspora-and-the-anti-facebook-why-alternative-social-networks-cant-win.html

[5] https://phyks.me/2015/01/why-i-am-quitting-diaspora.html

[6] https://medium.com/@badrihippo/you-deletefacebook-what-next-ff247b7b2543

[7] https://dayssincelastfacebookscandal.com/

[8] https://fediverse.party/

[9] https://www.theverge.com/2019/7/12/20691957/mastodon-decentralized-social-network-gab-migration-fediverse-app-blocking

Fediverse (Bild: servus / Davide Bevilacqua)