The dictionary defines the computer as »an automatic machine for processing information, obeying programs formed by arithmetic and logical sequences«. Although the words used seem clear, the definition is nonetheless abstract, which makes it difficult to visualise an image of the computer other than the one we all already have in mind. Yet the history of computational systems goes back to antiquity, and computers have taken different forms in the past alongside those that have been popularised thanks to technological evolution. In her project Form for Fluid Computer, Ioana Vreme Moser explores an alternative form of computer, based on a forgotten technology, and with it, a new narrative of our future. As part of the Research Labs organised by the servus.at association which in 2025 spotlight slow computing, the artist is preparing ways of communicating about fluid mechanisms by designing a workshop and a dedicated publication.

Foto: Codre Isac

As Ioana begins to develop her research, she has two concerns. The first one is related to computer models: long before the automated and digital systems we know today, devices were designed to decode the world around us. Let‘s take the astrolabe: it is a tool that was used throughout Antiquity and the Middle Ages by navigators and astronomers from the four corners of the world to find their way in time and space. It consists of several superimposed discs, each representing a distinct function, which, when combined by a rotating mechanism, calculate the height of the stars and their direction. By calculating the variations of quantifiable physical data, it makes it possible to model the problem and solve it. These elements define an analog computer.

Ioana‘s second concern is the history of the components and their political implications: the design of our current digital computers involves the extraction of mineral resources, generally from poor countries often hit by war, where the workforce lives and works under appalling conditions. There‘s no need to go into detail about all the stages involved in these methods, but it‘s clear that the production of a new device undeniably causes an avalanche of social and environmental impacts that are considerably harmful and deliberately kept invisible by the tech industries.

With this as a starting point, and given the multitude of catastrophic scenarios linked to our future, the artist asks one question: if all the super-sophisticated computer systems on which we depend were to disappear overnight, how would we manage to establish communication? Ioana knows that the key element in the functioning of electronics is the transistor, a component that has the ability to modulate and amplify electrical signals thanks to a material called a semiconductor. As the name suggests, its electrical conductivity is halfway between insulating materials and metals, and this feature allows the amount of current flowing through the transistor to be controlled. Their manufacture is extraordinarily complex, having reached levels of technological sophistication never seen before, and is the subject of considerable economic stakes, even resulting in a technological war between superpowers. Conscious of the entanglement between natural resources and politics, the artist looks for alternatives and discovers that it would be possible to imitate their properties by recovering materials that we have at our disposal, such as the galvanised sheet metal used for roofing when it is heated in certain areas. She designs a series of workshops on the subject called Politics of Parts.

Alongside her experiments, she continues to look for other amplifier systems and stumbles upon fluidics, a field that relies on computation through the movement of water streams. It‘s 2019, Ioana is doing research, but finds very little information online, the subject being rather niche. So she starts to draw prototypes without understanding 100% how it works. It is only in 2022 that she resumes her research at the library of the Technische Universität Berlin, which has an important archive on fluidics. One of the first water-based analog computers, called a »hydraulic integrator«, was designed in 1936 by Vladimir Lukyanov, the principle being to replace the mechanical process with water. In 1957, American researchers filed patents for their new creation, the fluidic amplifier. To visualise it, imagine a system of interconnected tanks and tubes through which water (or other fluids such as air) flows. From the initial reservoir, water is pumped into tubes which form branching circuits. This means that not only can the path taken by the water stream be different depending on the pressure at which the water is pumped, but also that it can be controlled. The streams can be guided from right to left by a Coanda effect; as the stream meets a convex surface, it attaches to it and flows, it undergoes a deviation in its trajectory. Let‘s say you have a cup of tea in your hands and you pour it very slowly – the fluid attaches itself to the side of the cup and then flows out into the void when it has nowhere else to stick. In the same way, Ioana can create a logical command and direct the water stream where she wants it. In short, the water enters the circuit, follows a predefined path, resulting from a series of operations, and exits providing information. This refers to the basic elements of the analog computer.

Then, she has to define each channel to make sense of the information. She is inspired by MONIAC, an analog computer based on fluidic logic, created by Bill Phillips in 1949 to model the British economy. In his concept, water represents money, and money could flow down the tube of consumption into the tank of people‘s needs, in a completely transparent circuit. She also looks at World3, the computer simulation on which the 1972 Limits of Growth report is based. It is built on the following variables: population, food production, industrialisation, pollution and consumption of non-renewable natural resources. Bluntly, the report concludes: »the most likely outcome will be a fairly sudden and uncontrollable decline in population and industrial capacity«. At this stage of the project, this is precisely what interests Ioana.

She imagines an installation based on the MONIAC model in which we can transparently visualise our consumption of resources and the rate of global growth through two scenarios: »business as usual« in which – if we do nothing –, we will suffer the societal collapse predicted by World3, and an equilibrium scenario in which policies regulate consumption to build a sustainable model. Ioana is now working on mapping her circuit: in the World3 scenario, if the pollution rate increases, the water tank that represents it, will fill up by drawing from another tank that represents the world population. Or, on the contrary, the world‘s population will increase, letting the resources slowly drain away until the water disappears.

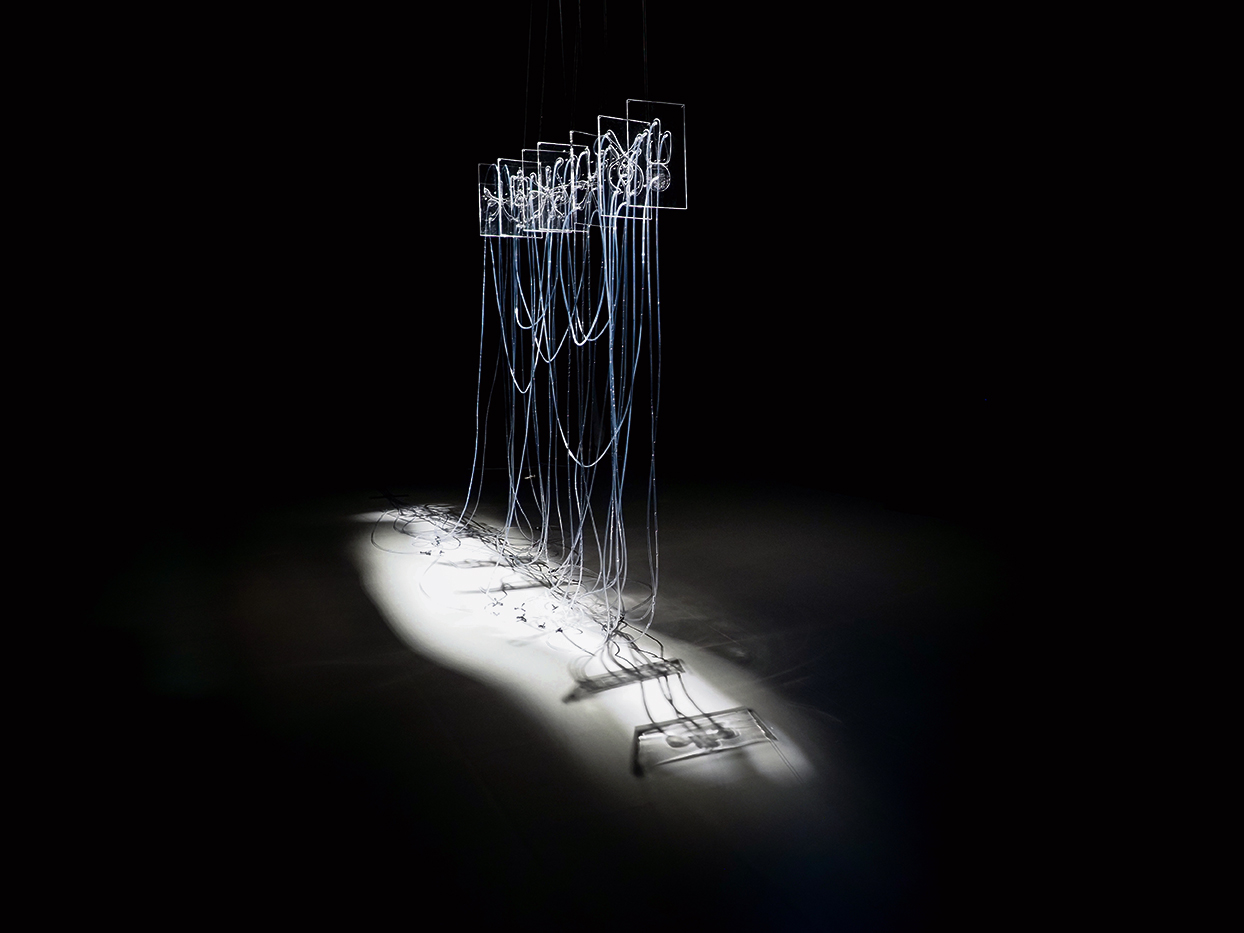

In reality, the materialisation of the project encompasses several iterations. Ioana produces a first installation called Fluid Memory, presented for the first time in 2019 at the STATE Studio in Berlin; she has glass elements made by a craftsman, which she then assembles and connects using plastic tubes, a vertical sculpture that evokes the image of a chemistry laboratory. Salt water circulates through the piece and accumulates in a coil, triggering sounds and rhythms that are supposed to echo human and computational memory. The concept of fluidics is there, but the artist will develop it further over time and through her research. In 2023, with Fluid Alphabet, she takes things up a notch; this time, she uses the design elements conceived for the fluidic systems found in the archives, based themselves on the shape of the mouth and throat cavity to create a new alphabet, ready for assembly. So far, she has gathered around thirty shapes, each with a particular function for the installation. In practice, each »letter« is engraved into the heart of a hermetically sealed plexiglas plate, which are then linked together by tubes. That same year, she presents the installation at the Klang Moor Schopfe biennial and at the NØ SCHOOL Nevers, alongside a series of workshops dedicated to fluid theory which she combines with Politics of Parts, and then again in the AfterLand group exhibition in Bucharest in 2024. In a recent exhibition at Berlin‘s Meinblau Projektraum, she showcases Fluid Anatomy, a new variant that takes the morphology and concept to a new level.

The aim of this research is not to illustrate precise data, but to make the fast pace of today‘s world visible and to visualise the potential benefits of putting a stop to it. Fluidics itself is a perfect example; until the 1970s, this model was competitive in the market, but its slowness and mass mean that a multitude of parameters have to be taken into account in comparison with electronics, which in turn has seen transistors become smaller and the power of digital computers grow exponentially. Slowing down has become essential to regaining balance, and that‘s the motto for servus.at this year. In April 2025, Ioana Vreme Moser and I are invited to take part in the Research Labs, which we dedicate to reflecting on the past history and alternative narratives that fluid computers can provide, and disseminating it through a collaborative publication.

By using fluidics as a technical process and by putting future scenarios into perspective, Form for Fluid Computer crosses the line into a political act. The project is a call to pause, to listen and to respect our own slow but steady rhythm, typical of a resilient nature.